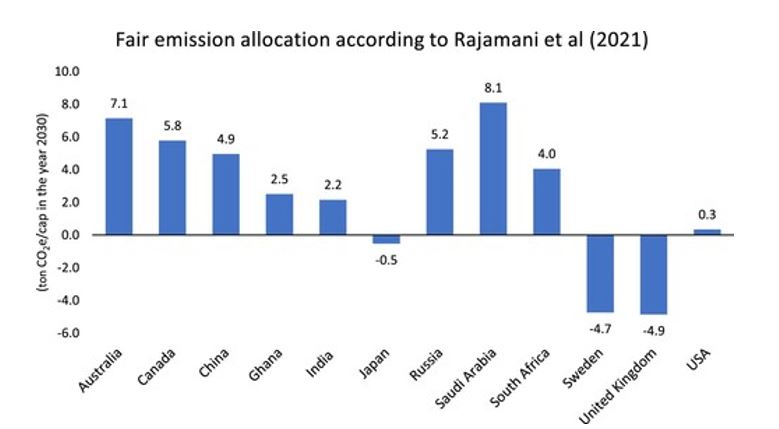

In a study from Mistra Electrification and Mistra Carbon Exit, Christian Azar and Daniel Johansson from Chalmers evaluate a proposal as to how the remaining carbon budget can be distributed among countries if the Paris Agreement’s goals are to be met. The starting point is a study carried out by Rajamani and colleagues in 2021 that proposed that high-emitting countries such as Australia, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Canada should be allowed to continue emitting much more carbon dioxide from Year 2030 than countries such as India and Ghana. The outcome for Sweden is that we should have negative emissions targets by Year 2030. (See the fact box and the graph below for more details).

“I believe very few people would think it’s fair to allow the countries that emit the most today to have the highest allowances in the future”, said Christian Azar.

The main reason why Azar and Johansson conducted their study is that it is highly concrete timely and relevant, and not merely academic in nature. In the Aurora case, a climate organization sued the Swedish State for having too-low climate ambitions, based on the Rajamani study. The case had been appealed to the Supreme Court in Sweden, but the court decided in February this year not to take up the case for review.

“It goes against all justice intuition that those who emit a lot per capita should be allowed to emit the most in the future. It’s a principle that almost everyone says is unreasonable from an equity perspective”, said Christian Azar.

Fair ways to share the remaining carbon budget

Azar and Johansson do not address in their study what a fair distribution of the emissions budget would look like. In a previous study, however, they looked at the possible guiding principles for Sweden and what they would mean for Sweden’s fair shares.

“One allocation could be equal allowances for all people. Another is that people in the poorer part of the world should get higher allowances, since people in the rich part have historically emitted more – this allocation approach is often referred to as historical responsibility. Yet another approach is based on capability, that is which capability a particular country has to reduce its emissions”, said Christian Azar.

A result of that study is that if one uses a per capita approach or an approach based on historical responsibility back to the mid-1990s, then Sweden’s current targets are in line with the Paris Agreement (i.e., that Sweden carries its fair share of the global effort). However, if we go back to the 1980s or use an approach that is based on capability, then Sweden needs to set more-stringent targets.

“But which principle to use for allocation emission allowances, and how far back in time should one go if one uses an approach based on historical accountability are ethical questions. Science can never say what is the ethically right allocation approach”, said Christian Azar.

Assessment of the Uppsala Model

The paper by Rajamani et al. is not the only study that Azar and Johansson have looked at with respect to allowance allocations. Earlier, they scrutinised the work of researchers at Uppsala University who have proposed an allocation for Sweden as well as for Swedish municipalities. They have found that this relies on the principle of “grandfathering” (for countries in the global North), i.e., the countries that emit the most per capita continue to receive the largest per capita allowance. This means that the US gets to emit 3-4 times more per capita than Sweden.

In an opinion piece in Göteborgs-Posten, Azar and Johansson question whether the municipalities think this can be called fair and just, writing the following:

“One can also ask the 60 municipalities and regions that have adopted the ‘Uppsala model’ if this is reasonable. Even the Västra Götaland Region has relied on this method, and indirectly also the Gothenburg municipality. The central question is: Why should Swedish citizens reduce emissions extra drastically so that Americans can emit more?”

Christian Azar thinks it is incomprehensible that Swedish municipalities should use this model, saying:

“I wonder if those municipalities think that it’s reasonable that their tough goals are a consequence of countries like the USA getting a more generous allocation”, said Christian Azar.

Climate justice and a fair allocation of national greenhouse gas emissions

In the paper Climate justice and a fair allocation of national greenhouse gas emissions, published in Climate Policy, Christian Azar and Daniel Johansson, analyse a paper published by Rajamani et al. titled: National ‘fair shares’ in reducing greenhouse gas emissions within the principled framework of international environmental law.

Azar and Johansson find that the approach adopted by Rajamani et al. confers a high emission allowance per capita by Year 2030 to currently high-emitting countries, such as Australia, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Canada, and China. In fact, Rajamani et al. propose that these countries should get 2–3-times more allowances per capita than, for instance, India and Ghana, despite the fact that the latter countries have significantly lower per capita emissions, per capita income, and historical emissions. The allocation to Sweden is negative.

Thus, the approach taken tends to reward countries with high emissions per capita and discriminate against countries with low emissions per capita.

One conclusion of Azar and Johansson is that the method applied by Rajamani et al, is not likely be appropriate for use in national debates and policy processes regarding fair national emissions targets. If no convincing arguments are presented it should not be considered fair that heavily emitting countries should be given more allowances per capita than developing countries in the global South.